- Home

- Maikranz, D. Eric

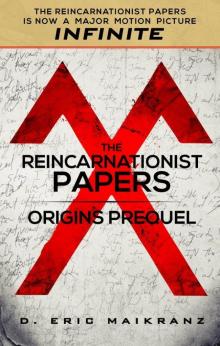

The Reincarnationist Papers - Origins Prequel Page 2

The Reincarnationist Papers - Origins Prequel Read online

Page 2

She flipped to the previous page and then back again to the final page. “It looks like a poem, Eric. Should I start reading it?”

“Yes, let’s start there and then go back to the beginning.”

She traced a finger over the handwritten stanzas one time and then began to read it a second time as she spoke the English words aloud. “I sing the song of a deathless soul, who fate and God made but does not control. Placed in most shapes and through many straits and lands, I roam. I launch at paradise, and I sail towards home. The course I there began will here be stayed, the sails hoisted there, dropped here, and anchors laid. For the great soul which here amongst us now does live, and moves that hand, and tongue, and brow. This soul, to whom Luther and Mohammed were prisons of flesh; this soul which often did tear and repair the cracks of the Empire of late Rome, and lived when every great change did come, had first in paradise, a low, but fatal room.”

She stopped and waited for me to catch up and finish writing the English translation in the new notebook. “The last line says ‘from The Progress of the Soul by John Donne 1573-1631’,” she concluded.

I finished writing these words and took a quick break to re-read them. “What do you think it means?” I asked her, while internally I asked myself the same question.

She reread it silently and then looked up at me. “I sing the song of a deathless soul,” she said aloud. “In the first part of the first notebook, he talked about living again like he would remember how he died if he killed himself in the noose.”

“That’s right,” I agreed. “The poem also says, ‘this soul which did tear and repair the cracks of late Rome lived when every great change did come.’ I wonder if the author of these notebooks felt the same way. Maybe he had some memory of the past that didn’t belong to him, and that is why he chose to add this poem at the end. It is interesting that the poem mentions Rome, the empire of late Rome, and here we sit in it.”

The waiter brought out two plates and set them on the table, breaking our concentration for a moment.

“How long do you have for lunch?” I asked.

She glanced up at the clock above the bar. “I only have an hour. Perhaps we should go back to the beginning?”

“I agree,” I said and handed her the first notebook.

“It looks like a short quote at the beginning,” she started and then read it aloud. “The stars I saw when I was a shepherd in Assyria look the same to me now as a New Englander,” she said. “The name on the quote sounds English, Henry David Thoreau. Do you know this name?”

“Yes, but not English. He was an American author 150 years ago.”

“Was he famous? I don’t know this writer, and I doubt that other Bulgarians like the man who wrote this would know him.”

“Americans know him.”

She flipped to the point where she had left off yesterday and read between small bites of salad. “What do you think it means when writes about having a perfect memory? Is this some sort of common saying in English?”

“Can you read the passage and translate it aloud for me?” I asked as I set down my fork and grabbed the pen.

She read to herself and then spoke his words out loud. “That’s the trouble with having a perfect memory. The benefit is that you remember everything that has ever happened to you. The drawback is that you can never forget anything that has ever happened to you. The former imparts wisdom, but the latter robs you of hope,” she said aloud and then continued. “Here is the part from yesterday, ‘I decided to write down this story with the certainty that I will look on it again with different eyes in a different time and remember who I'd been.’”

I shook my head. “It does sound like these notebooks are his story, but the perfect memory part and the certainty that he would read it again with different eyes in a different time reminds me of the Donne poem at the end.”

“That is what I think too,” she said, looking up at the clock again before returning to the handwritten page. “There is a word here that I do not understand. Do you know what is Minn-e-so-ta?” she asked, sounding out each syllable in the unfamiliar word.

“Minnesota,” I echoed back. “It is a state in the United States. It is in the north, next to Canada. What does he say about it?”

She continued reading and then started flipping forward in the notebook. “He says that he is from this place, Minnesota and that he moved to Los Angeles, where he lived for three years.”

“Los Angeles? Really?” I asked, thinking she must have read it wrong.

She paused and seemed to re-read the sentence. “Eric, I think the person who wrote this might be an American.”

“But you said he was Bulgarian and wrote like a native.”

“I said he wrote like a native Bulgarian but in an older style, like a grandfather.” She rifled through the pages, looking bemused. “I can’t be sure yet, but I feel like this story happens in America.”

“I don’t understand.”

“I don’t either, but let’s continue another time. I have to return to my work now,” she said, closing the notebook. “Can I take the notebooks with me? I can read them in my apartment to find out more.”

I was not ready for that question. Anxiety rose in me at the thought of the notebooks being with someone else. They seemed such an idle purchase two weeks ago, but now the notebooks seemed to hold some power over me. I had to solve their mystery. “How about we meet later, after work, or in your apartment? I would like to work on this together,” I said, collecting them.

“I live in the embassy, and guests are not allowed.”

“How about lunch tomorrow? I can meet you here again,” I offered.

She shook her head slightly. “I cannot, Eric. Tomorrow is Friday, and the ambassador hosts a weekly lunch with the embassy staff. I must attend. How about Saturday?” she offered.

I thought about my usual Saturdays giving tours. “Meet me in the Forum at 2:00 pm. I’ll prepare a picnic for us, and we can work for the rest of the day on this.”

“Let’s keep Sunday open as well,” she suggested. “Where in the Forum should I meet you?”

“You can’t miss me,” I said. “Just look for the crowds.”

Chapter 3

On Saturday at exactly 2:00 pm, I saw Marina walking toward me above the crowd of tourist families and couples surrounding me as I spoke about the history of the Roman senate. “This building behind me is a modern reconstruction of the senate, which at that time was called the curia. And it was not the first senate or curia. This one was called the Curia Julia, Julia, for,” I paused and waited for an answer that didn’t come. “Julius Caesar. Yes, it was Julius Caesar who designed this building behind me, but he never got to see it finished before he was assassinated.”

Marina approached and stood at the back of the crowd. I locked eyes with her and gave her a wink before continuing. “Let me tell you more about the death of Julius Caesar, but I want to do it in front of his temple. Please walk with me, and I will show you the temple of the divine Julius Caesar. Remember that this is a free tour, and you are welcome to join me and learn about the history of the Roman Forum. We’re going this way,” I bellowed as I raised a pointing finger and parted the crowd to lead the way.

I took a path through the crowd of four dozen tourists that put me within speaking distance of Marina. “Follow me,” I said to her directly as I led my flock to the center of the Forum, “and then wait for me.” She smiled and fell in with the walking crowd.

I waited for my group to reassemble in a semicircle around me as I placed my back to the simple brick structure, which was once the center of the world. “Behind me,” I began in a voice loud enough to carry to the outer ring of listeners, “is where Julius Caesar’s funeral was held. His body was burned on a pyre before vast crowds where you now stand, and he was declared a god by ordinary people like you and me. Reports from historians of the time tell us that Caesar was wildly popular and loved by the citizens of Rome and this murder at the hands

of senators was a shock that they could not understand. As the city mourned their slain leader, the citizens organized a funeral, and a pyre was built on this spot. Many senators and generals came to speak about Caesar’s faults and his accomplishments to crowds who wailed and tore their garments in sorrow. In the end, the crowds rushed the pyre and set it alight, declaring their fallen leader a god, a god worthy of a temple, the foundations of which you see today.”

I looked at the crowd around me, who gazed at the simple stones behind me and could now see some meaning there. “One can almost imagine the emotion on that day over two thousand years ago when a young senator named Mark Anthony stepped forward to speak and might have said similar words to those imagined by Shakespeare.”

I paused for a moment and began with those familiar words that concluded each tour. “Friends, Romans, countrymen, lend me your ears. I come to bury Caesar, not to praise him. The evil that men do lives after them, and the good is often interred with their bones. So let it be with Caesar,” I started and could see the wave of recognition wash over the faces around me as I performed this speech that was always the big close of each tour. I continued the delivery by heart and surveyed the crowd, making sure I focused my words on those I felt would want another paid tour with me.

“Bear with me, my heart is in the coffin there with Caesar, and I must pause ‘til it comes back to me,” I concluded and lowered my head to let the words hang in the air until the first claps came, which gave way to applause from every hand.

“Thank you,” I replied, “I hope you have enjoyed this free tour and that you have a better appreciation for these scattered stones about you. I offer other tours of Rome’s important sites like the Colosseum, St. Peter’s Basilica, and the Vatican museums. I will be leading a Vatican and St. Peter’s tour tomorrow, and I have a limited number of spots available. You can sign up for tomorrow with me right now,” I said, taking off my cap and tipping it toward them, “and you can leave a tip in my hat if you have enjoyed this tour. Thank you, and enjoy Rome.”

I reached into my backpack around the wine and snacks I had prepared for Marina and readied my appointment book for tomorrow’s tour reservations as men and women stepped forward to book a tour and leave a tip for me.

After twenty minutes of taking reservations and deposits, Marina stepped forward and placed a blue 10,000 Lire note in my cap that was filled with bills. “That was amazing,” she said. “You are a great speaker, and you know a lot about Rome.”

“Thanks, Marina,” I said, taking the blue note out of the hat and handing it back to her, “but you don’t need to do that.”

She refused the bill with a protesting hand. “Take it. You said you paid 20,000 for the notebooks. 10,000 from me would make us partners now, right?”

I smiled and liked where this was going. “Partners,” I said, extending my hand.

She shook my hand and then pointed to the open backpack on the ground at my feet. “Are they in there?”

“Yes, along with a treat for us,” I replied. “Come with me. I have a special spot I want to show you.”

I grabbed the backpack and started walking to the back edge of the Forum past a disused administrative office and a rear entrance ramp that was usually closed. I walked around the old office into a hidden cloister of trees that ringed a small open square filled with remnants of stone columns and blocks that looked like scattered puzzle pieces of a long broken empire.

“What is this place?” she asked.

“It is my favorite place in all of Rome. It has no historical significance within the Forum,” I said, walking to the back corner where three marble blocks sat forever estranged from their god’s lost temple. “I asked an administrator once, and she told me that these are leftover pieces from restorations, and they don’t know where they go or what building they belong to.” I set down the backpack on the middle stone. “I like taking my lunch here on these blocks. It feels like I have a special place all to myself.”

“It is peaceful here,” she said, taking a seat.

“I thought we could have a picnic here while we read more of the notebooks.”

“Excellent,” she said, taking them from my hand as I laid out bread, cheese, salami, olives, and wine. “I must admit I have had a difficult time sleeping for the past two nights, thinking about what we might find.”

She opened the first notebook and fell immediately into reading. ”I hope you don’t mind if I start.”

“I don’t mind if you start,” I said as I set out two short glasses and poured red wine, “so long as you share the details with me.”

“Yes, yes, of course,” she said, finding her place again in the handwritten text. “I suggest you get your notes ready, Eric. As I intend to read as much of this as I can today.”

“Okay,” I said, holding out a filled glass for her. “But first, a toast.”

She looked up from the text and took the glass. “To our mystery man,” she said and clinked her glass against mine, then drank the entire glass in one healthy gulp and looked for me to do the same. “In my country—in our country,” she corrected, placing her left hand carefully over the handwriting in the notebook as if to include him. “In our country, it is a tradition that we must finish our drink after a toast, and always if we toast a person.”

“To our mystery man,” I said and drained the glass.

She smiled in approval. “I have a theory about this man and his notebooks,” she said, holding her glass out for a refill, “but I don’t want to tell you until I can read more.”

“You have been thinking about this, Marina.”

She dropped her head back into her reading and offered ongoing commentary in English. “The first thing is, he writes this in the first person, so it is very personal. He talks mostly about himself and what is happening to him.”

I opened my notes and began writing along with her.

“Aha!” she exclaimed. “I knew we would get to it. Here he meets someone else, and the other person says his name.” She paused for a moment as if practicing the name. “It is like Ivan but with an E at the beginning. Do you say it like Even?

“Evan. We pronounce it Evan.”

“Evan,” she repeated. “This is not a Bulgarian name. Is it common in America?”

I tilted my head at the question. “It is not uncommon.”

“Not uncommon,” she chuckled. “You speak like a bureaucrat.”

“Here, have something to eat,” I said, offering her a sandwich as I looked up at the square of open blue sky framed by the swaying treetops.

“I knew from my first glances at these notebooks that he speaks with others, and that they would speak his name. I hope we get his full name. When we do, I can do some research to try to find him.”

I thought about the state resources she might be able to use behind the closed doors of her embassy but let those forming questions float from my mind.

She read for several uninterrupted minutes and took small bites of the sandwich.

“Marina, you have to share with me. I can’t just sit here and watch you read all day.”

She nodded and continued. “Here is an interesting bit. He is American. He grew up in Minnesota,” she said, struggling with the word again, “but he has all of these Bulgarian things around him like books and newspapers in Cyrillic. And then he writes about why.” She let the sentence drift away as she started reading again.

“Marina!” I protested.

“He says that he started getting something like visions that were very vivid like memories, but that they were not his. Evan writes that this started happening when he was seventeen, and they got stronger and stronger over the next year. He says that these visions were always in the first person, the same way that we all remember our memories.”

She looked up at me. “Think about your memories, even as a child. Think about if you see yourself in your memories or if you only see those people and things around you.”

I thought back to Indiana

, to my childhood friends, to my single mom. “You’re right. I don’t see myself. I only see others.”

“That is what he describes seeing, except the people and places and things that he sees are foreign and strange to him.” She continued reading for a while. “Here is what I was waiting for. He begins to hear those around him speak to him; again, it is like a memory, and they are not English. Eventually, he sees books and writing from these memories, and the writing is Cyrillic. It is Bulgarian.”

I jotted down notes as quickly as she spoke.

“These visions or memories get stronger and larger in number over the next year as he turned eighteen. He had so many of them that he was able to piece them together into a history, or as he says, into the memories of a life before his, in Bulgaria.”

“Wait, is that your theory…”

“Hold on,” she interrupted, her eyes scanning feverishly across the pages. “He says that he requested two Bulgarian books from the University of Minnesota.” She paused for a moment and looked up at me. “And Evan was able to read them from the memories of the life before in Bulgaria.”

“What?” I interjected. “Like he writes that he has skills in this life now as Evan that he got from these visions, from these memories of someone else’s life?”

“Or maybe it was his life before, and only now is he remembering?”

“Wait, is that what you think he’s saying?” I asked.

She nodded. “Think about it, Eric,” she said. “An American writes his story in a native, old-style Bulgarian that he never learned so that he could see it again in a different time with different eyes and remember who he had been. What do you think he is talking about here?”

I thought about her theory and the John Donne poem, and the Thoreau quote. “I see it, Marina, but I don’t know if I believe it quite yet. This whole thing could just be a story. ”

She cocked her head to the side as if surprised that I hadn’t pieced it together yet.

The Reincarnationist Papers - Origins Prequel

The Reincarnationist Papers - Origins Prequel