- Home

- Maikranz, D. Eric

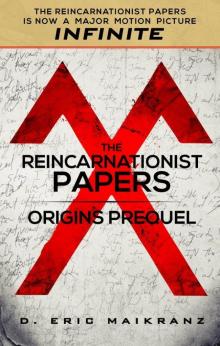

The Reincarnationist Papers - Origins Prequel

The Reincarnationist Papers - Origins Prequel Read online

PRAISE FOR THE REINCARNATIONIST PAPERS:

“a twisty, exciting adventure.” –Diana Gabaldon, #1 New York Times Bestselling author of The Outlander Series

“The Reincarnationist Papers is a book sprung from an imaginative premise: The existence of a secret society, called Cognomina, whose members have the ability to remember everything from their past lives.” –Oprah Magazine

“The high stakes and clever premise of Maikranz’s thrilling debut successfully evoke a sense of wide-eyed awe.” –Publishers Weekly

THE REINCARNATIONIST PAPERS

ORIGINS PREQUEL

™

By D. Eric Maikranz

Copyright © 2021 D. Eric Maikranz

Author’s Explanatory Note

The Reincarnationist Papers came into my possession while living in Rome at the turn of the millennium. I noticed the three plain notebooks in an antique shop on the medieval Via dei Coronari, just off Piazza Navona. At the time, I was conducting research for my first book, Insider’s Rome, a travel guide to some of the city’s more obscure but interesting sites. The notebooks seemed out of place in an antique store, weathered but not quite old enough. Idly picking up the first one, I was surprised to find it filled with Cyrillic handwriting. Being a speaker of Russian, the pages intrigued me, and I purchased them for a meager 20,000 lire, about $10 US at that time.

Despite lengthy efforts, I could not fully translate the text of the notebooks and eventually determined that they were Serbian or Bulgarian, not Russian.

Following a hunch, I first went to the Bulgarian Embassy on Via Pietro Rubens in north Rome. I struck up a conversation with Marina, an embassy staffer, and she confirmed the handwriting was Bulgarian. Intrigued by the first few pages, she agreed to help me translate it. Over the summer, Marina Lizhiva and I set to work translating, and we became enthralled as the story unfolded for us. When the translation was finished, I titled the compiled and translated work, as the original notebooks came with no title and were only numbered one, two, and three. I then set to work to verify what I could of Evan’s incredible story. That research is detailed as footnotes to the text, the only editorial work required after translation.

This short work is a detailed description of those discovery events in Rome and is a prequel to The Reincarnationist Papers.

D. Eric Maikranz

Chapter 1

“The primka looked ridiculous,” she mumbled to herself as she ran a long, elegant finger over the first handwritten lines in the first notebook. “Primka, primka,” she repeated as though trying to find the right word. “It is Bulgarian,” she replied without looking up at me, “but I do not know the English word for primka.” She looked tall and dominated her small desk in the front offices of the Bulgarian embassy in Rome. “It is like a when you execute someone with a rope,” she said in a thick Eastern European accent that sounded well steeped in the authority of service to the state.

“Hanging?” I offered, clutching the second and third notebooks in my hand.

“No, not exactly. Primka is the loop in the rope. The loop that you put around the neck,” she explained while mimicking a hanging rope with her long arm.

“A noose,” I replied.

She narrowed her dark eyes at me as though she did not understand. “News?” she challenged.

“No, not news,” I corrected with a smile. “Noose. That is the loop at the end of the hanging rope. Noose, like goose or loose but with an N.”

“Noose. Noooose,” she repeated and focused on the long U sound. She turned her eyes back to the first handwritten sentence in the notebook and then read aloud, ‘the noose looked ridiculous.’ She stopped and looked back up at me. “Does that sentence sound strange to you?”

I looked at her attractive face and its collection of odd angles at the intersection of straight nose and sharp cheekbones. “Yes. It doesn’t really make sense. What does it say after that?” I prompted.

She turned her head down to the page and began to read again. “It is Bulgarian for sure,” she said after a few seconds, “a native speaker.”

“All I know is that it is not Russian.”

“Do you read Russian?” she asked without looking up from her reading.

“Yes, that is why I purchased the notebooks.”

She shook her head as she read. “This was written by a man. I know this from the gender case he used as he wrote this. I think this man might want to end his life,” she continued. “He writes about thinking of different ways to kill himself, one way with the primka, the noose, as you say.”

I remained silent in hopes that she would continue reading. I was eager to know what was in the notebooks after struggling for weeks to translate individual words, single names, and a few phrases that were similar to the Russian I knew.

“This man talks about living again and remembering how he might die in this life,” she continued. “Let me read that part again.” She retraced her finger over the sentence and read to herself. “Yes, it says, ‘if you knew you would live again, not just believed it, but knew it, why would you not put your neck in that noose?” She looked up from the page. “What do you think he is talking about here?”

“I don’t know. What you are reading now is all that I know so far.”

“There is something here about a perfect memory and not wanting to relive the horror of dying alone with his head in the primka.” She stopped reading for a moment and furrowed her brow. “There is an old Bulgarian saying here that he hints at in this sentence. It is about the running rabbit preferring the snare, or the noose, to the jaws of the fox. It is a very old saying, like something a grandfather would use.”

She dragged her eyes from the page and met my gaze. “Do you think this man, this Bulgarian, is in trouble? Do you think he would hurt himself?”

“I don’t know. I don’t know who wrote it.”

She narrowed her eyes at me, and I could see that we would have to back up and start at the beginning. “You are American, yes?”

“Yes.”

“How did an American in Rome get these mysterious notebooks that were written by a native Bulgarian?” Her voice was flat and felt forged in a culture where information is like a currency that you collect onto yourself.

“You’re right. How rude of me. I should have started with that background. I am a journalist and author, and I moved to Rome this year to do some writing and research. I studied Russian in college, and I am always looking for ways to practice the language. Part of my research here in Rome took me to the antique stories on Via dei Coronari near Piazza Navona.”

“Go on,” she said without emotion.

“Well, I was looking around and taking notes for an article for American newspapers about shopping while on vacation. I saw these three notebooks, and they seemed out of place in an antique store. When I opened them, I saw the Cyrillic handwriting and thought they were Russian, so I purchased them for 20,000 lire, intending to read them. But when I tried to read them at home, I found that I could not. That’s when I suspected they were Serbian or Bulgarian. I don’t know any Serbs or Bulgarians. So I thought, what better place to find a Bulgarian speaker than in the embassy? And here I am,” I said, smiling.

She studied me for a long moment, as though waiting for more detail.

“That’s all I know about it,” I concluded, feeling a bit awkward under the weight of her gaze.

“Very unusual.” She eventually nodded and dropped her gaze back to the notebook and began to read again. She continued to skim the pages as she skipped ahead. “There is something about fire, a fascination with fire.” She jumped to the middle of the notebook

and began to read again. “This is a journal. No,” she corrected as she read. “Not a journal; this is more like a life story.” She flipped to the end of the first notebook. “There are other voices in here, other people that he describes.”

“Here is something interesting.” She turned the notebook to the side for me to see. “He writes, I decided to write down this story with the certainty that I will look on it again with different eyes in a different time and remember who I'd been.” She took back the notebook and closed the worn cover. “You said there were three notebooks. Can I see the other two?”

I presented them to her, and she started flipping through them. “It is the same; the same writing and the same voice.” A door closed somewhere behind her, and she rose from her reception desk in the lobby and gathered the three notebooks as though signaling that she needed to attend to an urgent task. She wore flat shoes and stood as tall as me when she handed the notebooks back to me. “Very interesting, is there anything else?”

I took the notebooks from her. “You have been a great help. Thank you for letting me come here and trouble you with this unusual request. Just knowing that they are written in Bulgarian is a big help and a start on what I need to do next.”

“And what will you do next?” she asked, casting a pensive glance over her shoulder toward the closed door behind her. “What happens next to this story that a man wrote to leave for himself?”

“I will get them translated. I really want to know the whole story now. Can you recommend anyone I could speak to about translating them?” I asked, holding up the three notebooks again.

She looked at the notebooks and then up at me for a few seconds. She wore a stoic expression that held few clues to her thoughts. “Come back tomorrow. I take my lunch break at noon. I would like to have another look when I have more time to focus on them.”

I smiled and nodded in agreement. “Perfect. I will be here tomorrow, Miss…”

She grew more anxious by the moment, “Marina, Marina Lizhiva. And don’t meet me here,” she said, taking a first leading step toward the front door. “Meet me at the café on the corner.”

I took her lead and walked quickly toward the entrance of the embassy. “Thanks, Marina. See you tomorrow,” I said as I pushed the door open.

“Wait. American,” she called out to me as I was halfway out the door. “What is your name?”

“My name is Eric.”

Chapter 2

I arrived at the café thirty minutes early and took a seat in the corner away from the other patrons. I ordered a tea and amaretto cookies, arranged the three notebooks first in a fanned out array, then in a neat row, and finally in a simple stack. I opened a new notebook that I had purchased that morning to capture the notes, if there were any, from this first meeting.

I didn’t know what to expect, and I tried to temper my enthusiasm for finding out more about the author of the notebooks and more about Marina. I reminded myself that only twenty-four hours ago, I knew nothing about them and now I had identified the language, determined that it was a man’s story, and found someone interested enough to help me unravel the mystery around them that had been coiling in my mind for weeks.

She arrived at precisely three minutes after noon, the time I estimated it would take to walk from the embassy. She saw me and walked to the table. “Priyatno,” she said, shaking my hand. “I think it is the same word in Russian, yes?”

“Priyatno, Marina,” I said, smiling. “Yes, it is the same. Please sit and join me.”

She sat but did not return my smile. “I have been thinking about the notebooks,” she said, looking down at them stacked on the table, “and I have been thinking about you.”

“Go on,” I prompted.

“I am interested in reading more and helping you to translate them if they are interesting, but I think it would be better if we started by getting to know more about each other first.”

“Sure,” I said, eager to know more about her.

“I wish for you to go first, please,” she stated and then sat back in her chair as a cue for me to begin. “Tell me about this American, who speaks Russian and now lives in Italy and walks into embassies without appointments to strike up conversations with strangers about manuscripts that he cannot read.” Her sharp face cracked into a slight smile as she finished her case.

“All right,” I said with a smile, trying to lighten the mood further. “I do admit it does sound a bit odd when you put it that way. How far back to want me to go?”

“To the beginning, Eric the American. Start at the beginning.”

“I was born in Indiana. It is a state in the middle of America and is mostly farms.”

“Did you grow up on a farm? You do not look like the American farm boy,” she said, letting her white smile peek out again.

“I did. I grew up on my grandparent’s farm.“

“Please continue. I want to know why an American farm boy,” she emphasized the last two words, teasing me, “would want to study Russian.”

“It was ten years ago in the late 1980s. It was the time of Glasnost and Perestroika, and Russia seemed like it could become a new place with new opportunities.”

“And how did you come to Rome?” she asked.

“I wanted to see The Vatican, St. Peter’s Basilica, and the Vatican museums.”

“And have you seen those things?”

I felt a satisfied smile cross my face. “I have done more than that, Marina. My apartment is two blocks from the walls of the Vatican, and I give tours of the Basilica and museums.”

“You are a tour guide? But I thought you said you were a writer and a journalist here?”

“I am both. To be a writer or a journalist requires a vow of poverty,” I said, with a wistful smile. “I write articles about Rome and Italy for newspapers back in America, but they pay nothing, and I have a contract to write a tourist guidebook on Rome, but they won’t pay me until the book is complete. In the meantime, I have to pay rent and eat. Speaking of that,” I stopped and looked around, “you must have limited time for your lunch break. Should we order our lunch?”

“Yes,” she said, raising a hand to call over a waiter who must have known her. “I will have salad, oil on the side, please,” she said to him in a fluent but accented Italian as though they had this exchange regularly. “And my American friend will have,” she paused for a moment and gave me a mischievous look before continuing in Italian, “a hamburger and a coke.”

“Pasta Bolognese and red wine, please,” I corrected in my basic Italian.

The waiter took our order, and I turned back to her, catching her staring at the notebooks. “What about you, Marina? Tell me about yourself.”

She stiffened a bit in her chair and surveyed the small café before starting. “Well, I am from Bulgaria from the town of Varna on the Black Sea.”

I waited for her to continue, but she remained silent and looked at me. “Is that everything?” I asked. “What about how you came to Rome or how you came to work in the embassy? Was your family in politics or foreign service?”

She shook her head once and continued, “I was invited to university to play volleyball because I am tall. It was there that I learned English and Italian. I was recruited into a position with the Bulgarian Foreign Service when I was still in school because of my language skills. That was the end of the communist time, and there was a lot of change. I was lucky to keep the same job until now.”

“Your English is perfect, Marina. Did you want to come to Rome?”

Her face brightened, and she looked out the window. “I wanted to go to America. I want to see New York and Texas and,” she paused for a moment, “Las Vegas,” she said, turning back to me. “Have you been to Las Vegas?”

I saw her interest and knew it could be a connection for us beyond the translation of the notebooks. “Yes, many times. What is it about Las Vegas that interests you?”

Marina leaned forward and rested her forearms on the table. “When I was

a girl, there was a show on television in our country. This was during the communist time. This program was meant to show how Bulgaria and the Soviet Union were the best at everything and how America and England were inferior and weak. This program said Las Vegas was a place where Americans threw their money away on games of chance and decadent shows.” She lowered her voice and continued as if sharing a secret with me. “They showed footage from a few of these Las Vegas shows, and they looked amazing. There was singing and dancing. The women wore the most fantastic costumes, and they were all so tall like me. They were as tall as men, and I imagined that every woman in America was my size and that I would fit in there better than I did at home. I studied and spoke English all the time in hopes they would send me to America, but I got Rome instead.”

“Do you like Rome?”

“Yes, I do,” she said, “but I want to go farther.”

“Farther away from Varna?”

The question seemed to catch her off guard, and she placed her long fingers on the stack of notebooks. “Why don’t we get started?”

I instantly regretted the probing question but was excited to start in earnest on learning more about the author of these notebooks. “I brought a blank notebook to write the translation in. Should we start with the first one again?”

She shook her head, pointing to the bottom one. “I want to start on the last one,” she said. “I want to see if there is a name or a signature.”

I reached over and grabbed the third notebook. “I thought the same thing. Marina, there is a name at the end, and there are quotes at the beginning of each notebook, but I don’t think those names are his,” I said as I handed it to her and flipped to the last page with handwriting on it. “I was able to translate the Cyrillic letters.”

She took the notebook and focused her eyes on the letters, “John Donne.”

“That’s right. John Donne was an English poet four hundred years ago,” I said. “I could translate that name and the name on a quote at the beginning, but those have been my only clues so far.”

The Reincarnationist Papers - Origins Prequel

The Reincarnationist Papers - Origins Prequel